March 2022 - quality jobs, bullshit jobs, the so-called great resignation, and what managers can do about it

the recurring slap: March 15 was Equal Pay day

Many responses to the introductory text on communication in last month’s issue. Thank you. Thank you. It’s worth saying twice. The purpose of these newsletters is to prompt managers to think about their craft. That’s the purpose for you, the reader. The benefit for me is the conversations that ensue. And there were plenty this month. Thank you.

I cant’t address all of the conversations here, but I’ll share a quote and answer a question.

The quote was sent by reader Tom who writes

It jumped to mind as I was reading and I wondered if that quote was coming further down in the text.

It didn’t, but it’s a good one, so here it is:

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.1

My response to Tom was that

I was trying to answer the question: How do I know whether people got or understood what I told or wrote them? And I too often observed in my own life and in conversation with managers that the answer “well, I sent out an email” does not ensure understanding.

The question: How then do I ensure that I understood what the other person is trying to say?

A good place to start is Rapoport’s Rules of Argument:

a list of rules promulgated by the social psychologist and game theorist Anatol Rapoport (creator of the winning Tit-for-Tat strategy in Robert Axelrod’s legendary prisoner’s dilemma tournament).

They are meant to help one put together a “successful critical commentary” as well as “be charitable” to the person you are speaking with. Because the context of the rules is a discussion and possible disagreement, Rapaport calls the person you are talking to “the target”. Here are the rules:

1. You should attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.”

2. You should list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

3. You should mention anything that you have learned from your target.

4. Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.2

In my work with managers I often invite them to seek confirmation that they understood what the other person is saying by prefacing the “re-express” with phrases such as “If I heard you correctly, …” or “What I’m hearing you say is…” followed by the “re-express” in one’s own words and not simply a repetition of the other person’s words.

Another way of going at it is by figuring out how the other person’s ideas came about. I hear managers say “I know where you’re coming from”. However, rather than ass/u/me that we know, spelling it out allows the other person to confirm that we are indeed correct. Bertrand Russell states it as follows:

It is important to learn not to be angry with opinions different from your own, but to set to work understanding how they come about. If, after you have understood them, they still seem false, you can then combat them much more effectually than if you had continued to be merely horrified.3

In other words, conversation is necessary… and as soon as possible. What avoids the talking at is the quick response that seeks confirmation or clarification. Without that response to the original statement or argument, and a response to that response, we simply do not know whether the other party understands what you are trying to say. Last month, I called this

both parties making themselves co-responsible in creating a shared understanding.

In practice, the way to be co-responsible is to co-respond: to respond to what the other person is trying to say. Communicating is not talking at people, it’s co-responding.

Quote provided and question answered. Thank you for your comments and thank you Tom for the quote!

From my blog

The idea that you are successful because you are hardworking is pernicious… and wrong

A major study on the quality of work in the U.S.

What is a good job?

It’s not a philosophical question.

We’d rather do work we like, enjoy the people with whom we work, be treated decently by our manager and the company, earn a wage that covers not only expenses but allows for savings for a rainy day… than not.

I’ve shared a few sources about work and jobs in this newsletter before and some studies do not paint a bright picture. To the point of having a category now called “bullshit jobs”.

So I find this Gallup study [this is a pdf download] useful in that it designs the survey around a clear set of dimensions that make up a good job. Here they are:

Level of pay;

Stable and predictable pay;

Stable and predictable hours;

Control over hours and/or location (e.g., ability to work flexible hours, work remotely);

Job security;

Benefits (e.g., healthcare, retirement);

Career advancement opportunities (e.g., promotion path, learning new skills);

Enjoying your day-to-day work (e.g., good coworkers/managers, pleasant work environment, manageable stress level);

Having a sense of purpose and dignity in your work;

Having the power to change things about your work that you’re not satisfied with; and

The health and safety of your work environment.

I might not agree with all dimensions and some might be missing. Also, I would love to see a ranking of them.

In any case, I find these dimensions useful on at least two counts:

They’re a good start. It can help managers and business owners have healthy and challenging discussions about work that go beyond income and benefits; and

They provide an outline for managers and business owners to review what they are doing (and how well) about these and other dimensions.

Here are the findings:

First, the macro results:

Less than half of American workers are in good jobs;

Low-income workers are far less likely to receive employment benefits, from health insurance and retirement plans to maternity and sick leave;

Older workers, white workers and those with high levels of education are most likely to be in good jobs;

Among sub-baccalaureate workers, certifications are strongly associated with good jobs;

Workers in rural areas and small towns give higher job quality ratings despite lower average incomes;

Workers across income levels generally agree on the most important job quality dimensions;

Low-income workers are more likely to be “disappointed” with all aspects of job quality;

Most workers say their pay has improved in the last five years, but other aspects of their job have not;

Two-thirds of U.S. workers say they are currently in their “best job ever”; and

Job quality varies systematically by type of job (full time, part time, multiple), organization size, type of work, occupation, and sector.

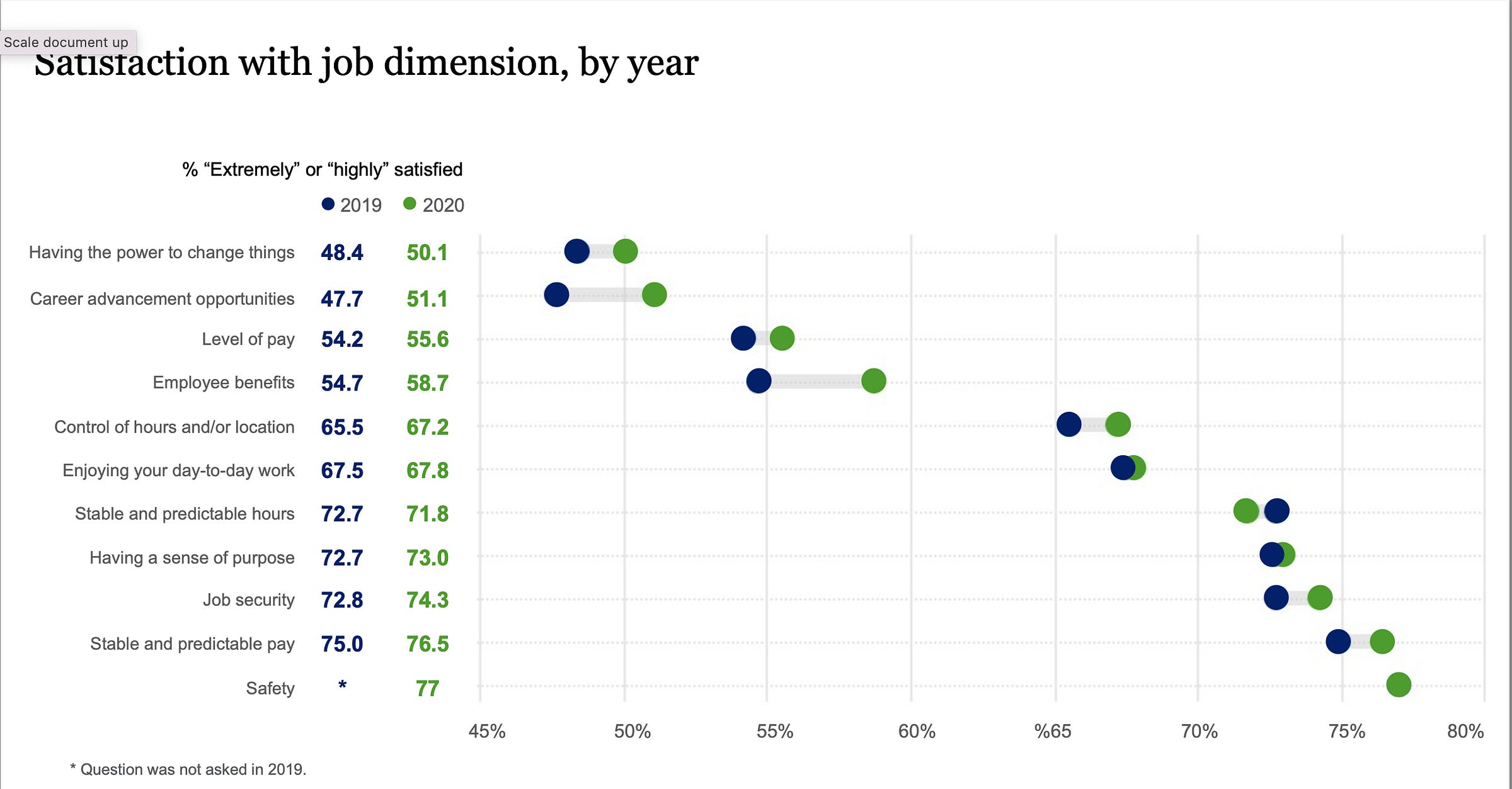

Since the original study was is from 2019, we also have comparative results from 2020 [this is a pdf download], that is, after covid-19 hit:

And the micro results stated as “more predictive than income or benefits”:

At work, my opinions seem to count;

At work, I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day;

There is someone at work who encourages my development;

I have the opportunity to learn new skills that will be valuable to my career;

I am expected to be creative or innovative at my job; and

I take risks at my job that could lead to new products, services or solutions.

These micro results are definitely in the realm of the day-to-day responsibility of managers. If you’re a manager, you can reflect on what you do (and do not do) that might have a direct impact of these specific dimensions.

For example, in line with my definition of communication, rather than ask yourself “Do I tell the people on my team that their opinions count?”, the question should be along the lines of “Can my team members recognize their opinions in the way I deal with them, the tasks I entrust them, changes in protocols and procedures based on their observations and suggestions, how much I delegate, etc.?”

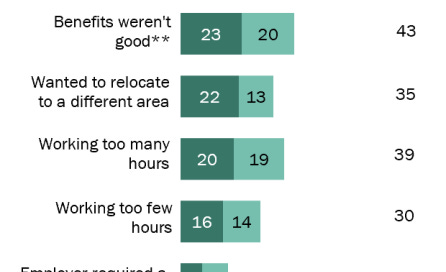

Why they quit in 2021

Much is being said about the Great Resignation and we are still speculating on the reasons why workers have been exiting en masse.

A Pew Research Center survey records the answers of 9,000+ respondents on why they left a job in 2021:

Low pay (63%),

No opportunities for advancement (63%) and

Feeling disrespected at work (57%).

At least a third say each of these were major reasons why they left.

I often hear that “people don’t leave companies, they leave bad managers” but I have never found any research that supports that assertion. However this survey suggests that it certainly is one of the reasons why people leave companies.

I realize there are a lot of data to process this month, but I think the job quality dimensions and the results from 2019, 2020, and 2021 offer a lot of food for reflection on your management practice. Once you’ve given it some thought, drop me a line on what conclusions you draw from it all and what changes you plan to implement.

I’m sending this on the 2nd to avoid any misunderstanding of a possible April Fool’s prank.

See you next month!

Richard

The quote has recently been attributed to George Bernard Shaw. Apparently William H. Whyte should get the credit

Daniel C. Dennett, Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking (2013).

Bertrand Russell, The Art of Philosophizing and other Essays (1942), Essay I: The Art of Rational Conjecture.