April 2024 - most work is new work, learn to change your mind, don't hoard talent, and what's better than feedback

issue #63

Welcome to what “crossed my desk” on this month of fools and eclipses.

This is an excellent write-up of an academic paper on employee hoarding. Key takeaway:

Talent hoarding is bad for organizations, employees, and managers themselves. [M]anagers should keep the following points in mind when considering their own leadership performance.

Managers must be willing to give up talent if they wish to become talent magnets;

Letting people move on is good for organizations and managers;

Employees know which managers hoard talent;

Hoarding is costly.

Organizations that wish to discourage hoarding should consider seriously incentivizing managers to develop their employees and facilitate their advancement to other areas of the company.

Seth Godin makes a distinction between manipulation, indoctrination, and addiction.

They happen in organizations and they are toxic. Avoid them. Call it out when you see it. Go slow because “once they begin, they create the conditions where it’s ever more difficult to stop.”

Steven Levy interviews Google employees for the inside story of the invention of modern AI

Eight names are listed as authors on “Attention Is All You Need,” a scientific paper written in the spring of 2017. They were all Google researchers, though by then one had left the company. (…)

Approaching its seventh anniversary, the “Attention” paper has attained legendary status. The authors started with a thriving and improving technology—a variety of AI called neural networks—and made it into something else: a digital system so powerful that its output can feel like the product of an alien intelligence. Called transformers, this architecture is the not-so-secret sauce behind all those mind-blowing AI products, including ChatGPT and graphic generators such as Dall-E and Midjourney.

The Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) puts out an AI Index every year. The report tracks, collates, distills, and visualizes data related to artificial intelligence. The 2024 Index is its seventh report.

The top takeaways:

AI beats humans on some tasks, but not on all.

Industry continues to dominate frontier AI research.

Frontier models get way more expensive.

The United States leads China, the EU, and the U.K. as the leading source of top AI models.

Robust and standardized evaluations for LLM responsibility are seriously lacking.

Generative AI investment skyrockets.

The data is in: AI makes workers more productive and leads to higher quality work.

Scientific progress accelerates even further, thanks to AI.

The number of AI regulations in the United States sharply increases.

People across the globe are more cognizant of AI’s potential impact—and more nervous.

When another person points out the flaws in your behaviour, your first inclination might be to push back and make excuses for yourself. This is the phenomenon known as rationalisation, in which people shield themselves from taking criticism seriously by erecting a scaffolding of biased reasons against it.

Feedback is good, but there is a better way to discover our flaws: reading fiction.

I agree with Roger Martin on many things, including that “a plan is not a strategy”. I also agree with this: managers and their teams should celebrate more. Wins, progress, learnings, big and small.

Hala Alyan on the ability to change your mind:

[C]hanging one’s mind is an art form in and of itself—a practice of endurance and flexibility. It resembles marathoning or playing an instrument: something that gets better the more you do it, with an element of muscle memory. It necessitates exposure to new information and ideas, goodness of fit in terms of the timing and delivery of that information, and one’s own predisposition to cognitive adaptability. It is a process of privilege. One must have access to information that can change one’s mind, one must have the temperament and time to absorb it.

Jonathan Haidt has a new book out that I meant to read. Then I came across Candice Odgers' book review in Nature:

Two things need to be said after reading The Anxious Generation. First, this book is going to sell a lot of copies, because Jonathan Haidt is telling a scary story about children’s development that many parents are primed to believe.

Second, the book’s repeated suggestion that digital technologies are rewiring our children’s brains and causing an epidemic of mental illness is not supported by science.

Worse, the bold proposal that social media is to blame might distract us from effectively responding to the real causes of the current mental-health crisis in young people.

James Heskett wrote 287 columns on a variety of management-related topics for Harvard Business School’s Working Knowledge. I have been inspired by many of them over the years. In his farewell column he shares this factoid:

The column drawing the most comments from among the 287 columns was “Why Isn’t ‘Servant Leadership’ More Prevalent?” in 2013. Many respondents posed the question of whether or not the term “servant leadership” was an oxymoron. Obviously, the topic was on the minds of many.

Oxymoron. What do you think?

From a paper on “The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018”:

We estimate that about six out of 10 jobs people are doing at present didn’t exist in 1940. A lot of the things that we do today, no one was doing at that point. Most contemporary jobs require expertise that didn’t exist back then, and was not relevant at that time.”

This finding, covering the period 1940 to 2018, yields some larger implications. For one thing, many new jobs are created by technology. But not all: Some come from consumer demand, such as health care services jobs for an aging population.

On another front, the research shows a notable divide in recent new-job creation: During the first 40 years of the 1940-2018 period, many new jobs were middle-class manufacturing and clerical jobs, but in the last 40 years, new job creation often involves either highly paid professional work or lower-wage service work.

Finally, the study brings novel data to a tricky question: To what extent does technology create new jobs, and to what extent does it replace jobs?

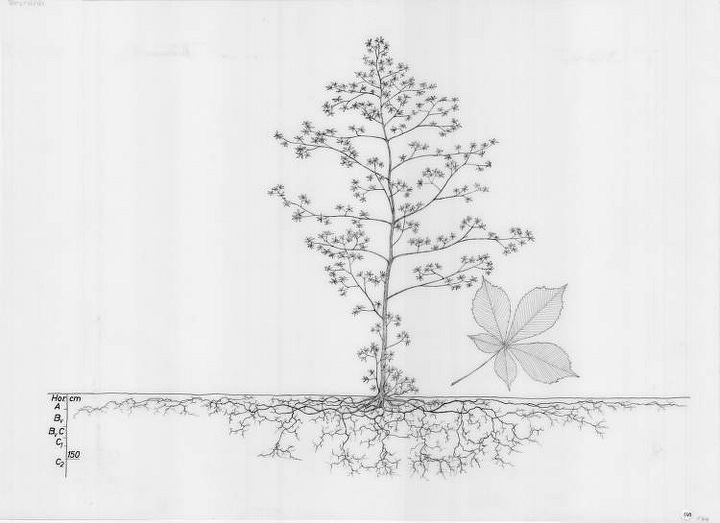

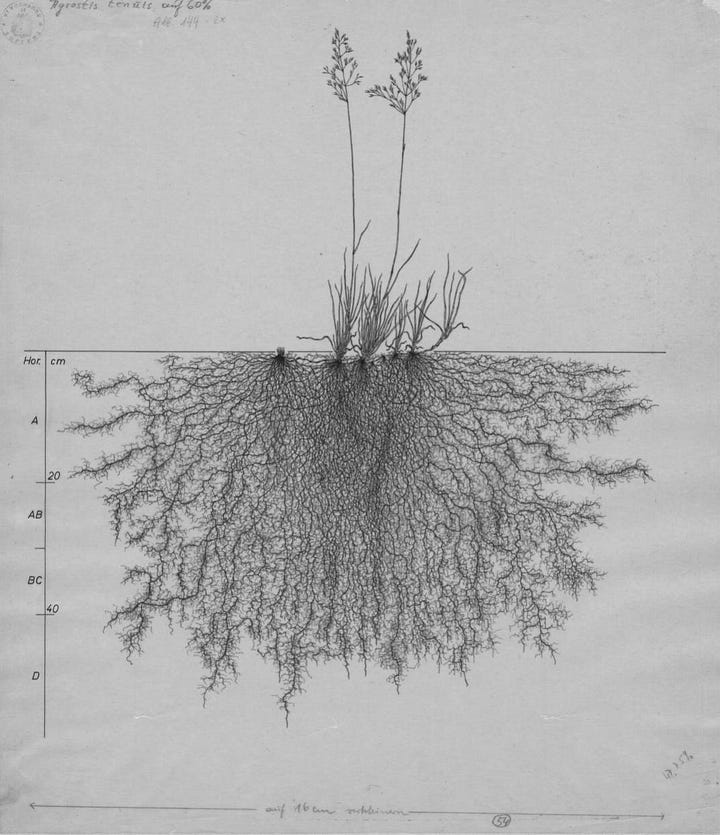

And now for something completely different

I’m just loving these root system drawings.