I was in a final-round interview for a senior leadership role. The panel had barely finished introductions when someone asked,

“What do you want your legacy to be?”

Not: What challenges are you most drawn to?

Not: What do you think the team needs?

Not: How do you approach complexity?

Just straight to: How do you want to be remembered?

It was a surreal moment. I hadn’t met a single team member. I hadn’t spoken to any customers, or seen the space where the work happened. I didn’t know the vision of the person I’d be reporting to, or what pressures they were under. Yet here I was, being asked to pre-script my postscript.

That question seems to have become the norm.

We’ve made legacy-talk a kind of performance shorthand. A way of signaling that someone is “thinking big.” But increasingly, it feels like a distraction. A premature obituary disguised as strategic vision. A way of skipping past the mess of the present in favor of a tidy imagined future.

In practice, I’ve seen it show up in quieter ways too.

A manager agonizes over how they’ll be perceived. Will I be seen as a visionary? A people-first leader? They start managing the story of their leadership rather than the work itself. Meanwhile, a difficult team dynamic goes unaddressed, a necessary decision is deferred, and an uncomfortable truth is avoided.

The desire to be remembered can subtly displace the work of attending to what’s needed right now.

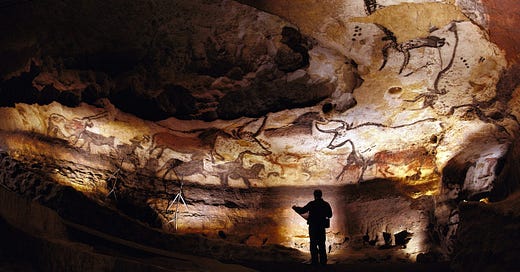

Walk through any city and you’ll see it in physical form. Streets named after people no one remembers. Foundations whose namesakes are long forgotten. Buildings with gilt-lettered donor walls that patients hurry past on their way to the right room. These supposed monuments to legacy reduced to wayfinding aids. Turn left at Johnson Avenue. Room 312, across from the Hastings Wing.

Even the grandest names eventually blur into background noise.

Jonas Salk seemed to understand this. When asked who owned the patent on his polio vaccine, he famously replied, “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

He could have built a pharmaceutical empire. He could have carved his name into the landscape of institutions and endowments. Instead, he focused on getting the vaccine into as many arms as possible, as fast as possible.

The result? Real, lasting impact. Not in how he’s remembered, but in the children who never needed iron lungs. In lives quietly preserved.

Had he pursued legacy, he might have become another name on a building. Instead, he became part of people’s lives.

That’s the irony. The ones we remember most often weren’t chasing remembrance. They were thinking about what the people around them needed right now.

We’ve gotten it backwards.

Too often, we ask leaders about their legacy before they’ve even earned the right to have one.

If you’re a manager, the people you work with won’t remember your “legacy.” They’ll remember if you listened. They’ll remember if you backed them when it counted. They’ll remember if you made a path for them to grow, or closed it off. They’ll remember if you helped them become more of who they were, or made them feel smaller.

Most of that won’t show up in a keynote or on a plaque. It’ll show up in someone else’s work: the choices they make when you’re not around and what they pass on to someone else.

Legacy isn’t something you declare. It’s something you leave behind without knowing you left it. And it usually begins by paying attention to what’s in front of you.

==

Whenever you’re ready

Here are ways we can work together:

Facilitation — I help teams think clearly and work cohesively—whether you're shaping strategy, aligning on priorities, or developing trust. Designed conversations that move your work forward and bring out your best thinking, together.

Leadership Coaching — One-on-one conversations that help you clarify decisions, navigate complexity, and lead with greater focus and integrity. A thinking partner when it matters most.

If you’d like to discuss how any of these might fit your current situation, reply to this email. I’m always happy to chat.